Originally posted January 9, 2014. Full post here: https://darrenblaney.blogspot.com/2014/01/could-denton-welchs-in-youth-is.html

Set mainly in the environs of an upscale hotel in the British countryside at which Orvil is staying with his mildly effete wealthy father and two condescending older brothers, Denton Welch’s mid-20th-Century novel In Youth Is Pleasure chronicles the vibrant inner life of Orvil Pym, a sensitive and imaginative teenage boy who is just coming of age. The narrative offers a seemingly unrelated sequence of events, built around the various illicit pleasures Orvil experiences over the course of his summer vacation after a debilitating first year at boarding school. Left to the endlessly entertaining devices of his own amusement by his distant father and annoying elder siblings (whose reaction to Orvil’s presence ranges from teasing to embarrassment to total disregard to fraternal protection – the one closer in age is relatively kind if a bit gruff, while the eldest is the most overbearing, fear-inducing, and cold), Orvil explores the hotel, its grounds, and surrounding countryside without supervision.

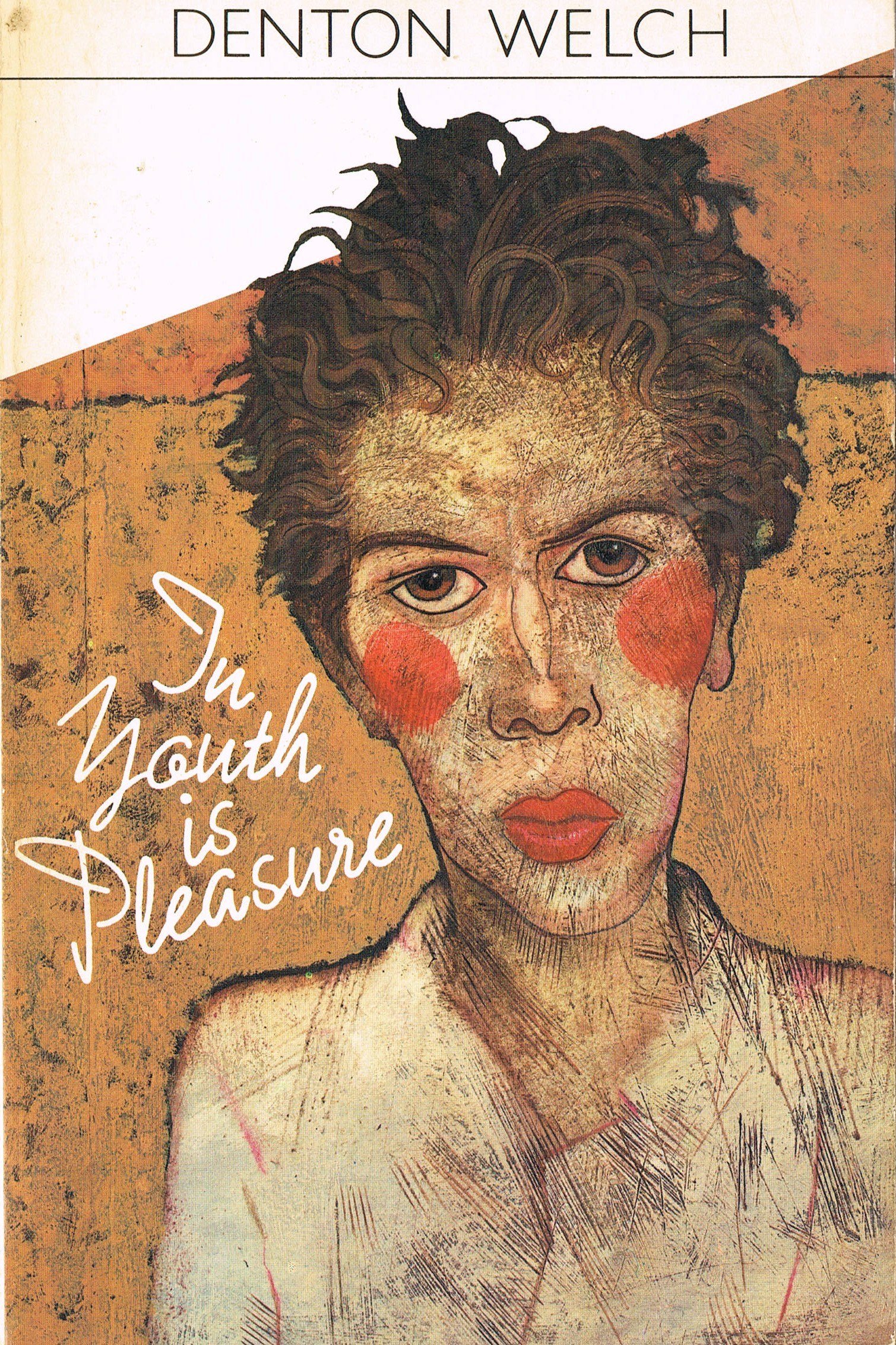

Over the course of the novel’s 152 pages, Orvil engages in various activities that could be described as transgressions against the ‘normative’ expectations of male teenage behavior. For example, he steals a tube of lipstick from a department store, then hides it in the back of a drawer in his hotel room, only to coat his young lips with the cheap sticky waxy-tasting paint several chapters later while admiring his mirror, before applying it freely over his bare body as if it were tribal war paint, encircling his nipples with the bright red pigment, creating gash marks alongside his ribs and forehead, etc., then dancing about wildly in his hotel room before scurrying frantically to wipe it off, jolted into action by his elder brother’s door knocks.

Other examples of Orvil’s ‘queer’ behavior include his breaking into a Catholic Church and becoming drunk on stolen altar wine while exploring the various nooks and crannies of the church including the inside pockets of the neatly-hung choir robes, and his fascination with a book in the hotel lobby dedicated to physical exercise that features photographs of semi-naked male athletes demonstrating the movements. Most beguiling for this reader was Orvil’s rainy day interlude with a ruggedly sunburnt parson in a cottage in the woods that begins with an invitation to warm himself by the wood stove, climaxes in his exploration of the feeling of the inside of the parson’s leather shoes that he’d been instructed to polish, and ends in Orvil’s binding the priest’s hands and feet with white rope before a rapid no-turning-back exit in spite of the cleric’s pleas for him to return on the following day. More innocuous passages narrate Orvil’s delight in finding the perfect broken China saucer to buy at an antique store, or in taking afternoon tea in the hotel lobby after an afternoon spent canoeing alone, in which a dive into the river precipitated the joy of weightlessness amidst the flowing water, followed by thrilling heat of the sun as he lay on the riverbank to dry.

What makes the novel most engaging is the way that Welch’s seductive, evocative prose captures the delights of youth objectively yet with palpable balminess: the writing – in third person omniscient voice – allows the reader to indulge in the unjaded feeling of interacting with an endlessly alluring world that is seemingly full of possibility, but is nevertheless clouded by the constricting feeling of social expectation that becomes ever more omnipresent with the encroachment of adulthood.

Reading the book brought back rich memories of my own adolescent fantasies of living alone in a cave in the woods, where I’d hoped to survive far from the imprisoning demands of modern society, free, and in harmony with nature’s rhythms (obviously these fantasies tended to arise more often in summer than in the bone-chilling dead of winter!), as well as my own real-life adventures breaking into the local church at midnight to play the pipe organ with my childhood friend.

Although cycles of violence between men, initiation into manhood, and denied yet ubiquitous homoerotic impulses are predominant themes in the narrative, Orvil’s imaginative inner life is punctuated by visits with slightly older adolescent women, whom Orvil sees as appealingly nubile and yet comfortingly maternal. His desires for these women provoke him, yet his inability to attain them (beyond receiving a protective kiss or sympathetic gesture of affinity) seems to augment the pervasive feeling of loss he has felt in wake of his mother’s death three years earlier. His infatuated fixation on Aphra, a voluptuous maiden, culminates when, in a pitch black, dank, yet regally-appointed cave near the hotel that had been used by King George IV as an entertainment grotto, he catches glimpses of her bare body enwrapped around his elder brother Charles. To cope with his unrequited lust, Orvil fantasizes that his brother is a giant baby to whom Aphra feeds her milk. His interactions with his friend Constance and her mother Lady Winkle are perhaps less traumatic, though equally disappointing. The theme of initiation/abuse proves to be cross-generational and trans-gender rather than specific to his age or sex: when mailing a letter, Orvil takes momentary pleasure in bringing a baby in a pram to tears by making hideous faces at it. In the next chapter, he feels sympathy for a 90-year-old grandmother whose servant caregiver forbids her to play her piano despite the fact that it is the only activity at which she seems to take any pleasure in her decrepitude.

Orvil’s fantasies of escape and emancipation continue to intensify throughout the narrative. Without giving away the ending completely: in the last chapter, the moment of bullying that occurs on the return train to school is set off refreshingly with a moment of fraternal protection that gives the reader hope that Orvil will survive this awkward phase and find a way to transcend any taunting that might befall him in the coming year. Written in the early 1940s and published originally in 1945, Welch’s novel perceptibly both draws from and ignores Freudian psychoanalytic theory. It uses phallic, vaginal, and anal symbolism nonchalantly yet subtly, which tickles rather than assaults the imagination. Orvil’s character strengthens throughout the text and leaves open the possibility that despite the loss of naïve youthful pleasure and wonder that early adulthood will inevitably impose, Orvil will nevertheless emerge upon graduation much like Joyce’s young male artist: with a more refined ability to discover, indulge, and inspire himself.

In Youth Is Pleasure reminded me of a refined-if-distantly-British version of John Knowles’ A Separate Peace, if Gene Forrester in the latter had actually been more truly ‘separate.’ Without the foil of a virile Phineas to admire and mourn, Welch’s Orvil comes across as both more independently-minded and aloof, and yet also more queerly vulnerable in his self-sufficiency. It is not surprising that the rich artfulness of Welch’s portrait has appealed to such renowned writers as William Burroughs and Edmund White, who are clearly indebted to the clarity of Welch’s perception and to his magnanimous use of sexual imagery.

One can imagine how the more self-consciously accepting queer youth of today, who are unfortunately still too-often bullied in the 21st Century, might take inspiration from Orvil’s imagination and perseverance in the face of great odds, if not feel a bit jealous of the social standing into which he was born and from which he yearns to take flight.